|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

It's pretty clear that SpaceX is the most capable aerospace organization right now. More capable than NASA, the Russian ROSCOSMOS, and India's ISRO. Maybe there might be a discussion compared to the Chinese.

Many companies want to emulate SpaceX, and there is a lot of discussion about whether they will or not. Many of those discussions ignore the fact that SpaceX benefited from a rather unique set of circumstances when building Falcon 9.

In this video we're going to take a journey into the world of alternate universes and look at a number of situations that, if different, would likely have led either a drastically different SpaceX or no SpaceX at all.

I'm going to skip the early days of SpaceX, the days when they were working on Falcon 1. If you want to understand those days, read Eric Berger's excellent book "liftoff". We are going to focus on Falcon 9.

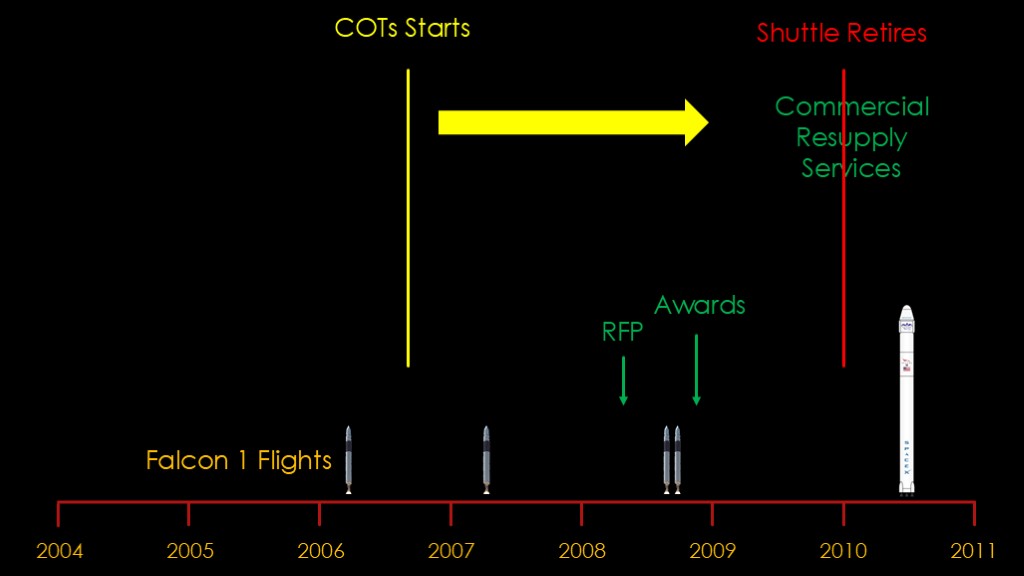

We know that the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011 meant NASA needed a way to carry supplies to the Space Station, and for that they created the commercial Orbital Transportation Services program, or COTs.

That led to SpaceX getting help to build Falcon 9 and Cargo Dragon.

That takes us to our first scenario:

Scenario 1: What if shuttle kept flying?

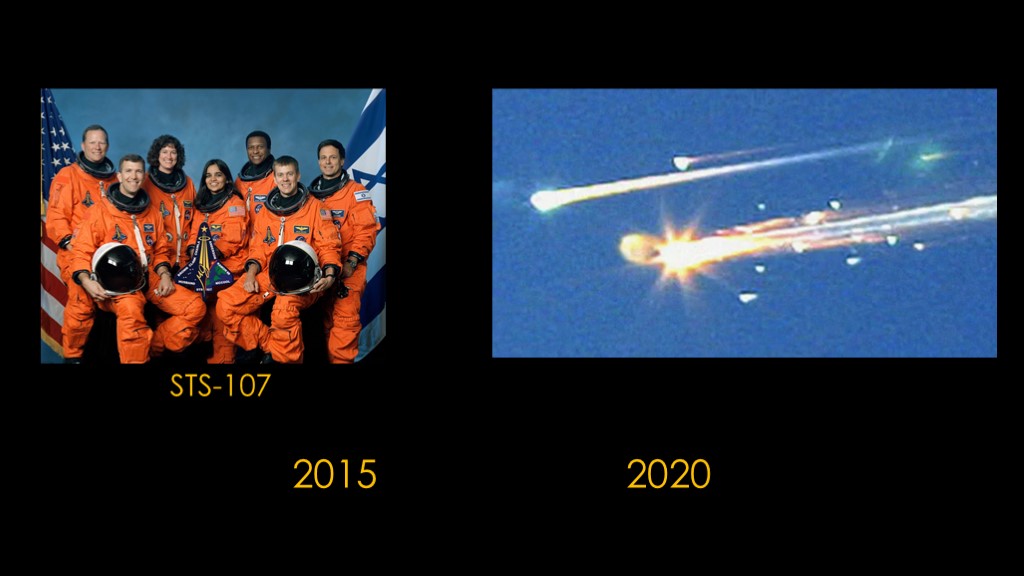

Columbia disintegrated on reentry in February of 2003, killing all 7 members of the STS 107 crew.

If the Columbia accident hadn't occurred - and if there no other losses of shuttle - shuttle could have flown to 2015 or even 2020, and the COTs program wouldn't have been available when SpaceX needed it.

After the accident, the Columbia Accident Review Board created a report that detailed the causes of the accident and made recommendations going forward. Not only did they detail the changes to make before shuttle returned to flight, they detailed what should be done to continue flying after 2010.

If that plan was followed - and if there were no further accidents - the shuttle could have flown to 2015 or beyond, eliminating the chance for SpaceX to get a COTs contract.

But president George W. Bush decided that he wanted a different space program, including a plan to return to the moon by 2020 in preparation for the human exploration of Mars. That new plan required the retirement of shuttle in 2010 after the completion of the space station so that the shuttle money could be shifted to the new exploration programs.

The new plan is what led to shuttle being retired, and would set the stage for SpaceX many years later.

Scenario 2: What if NASA had a replacement vehicle to service ISS, so that COTs would not be needed?

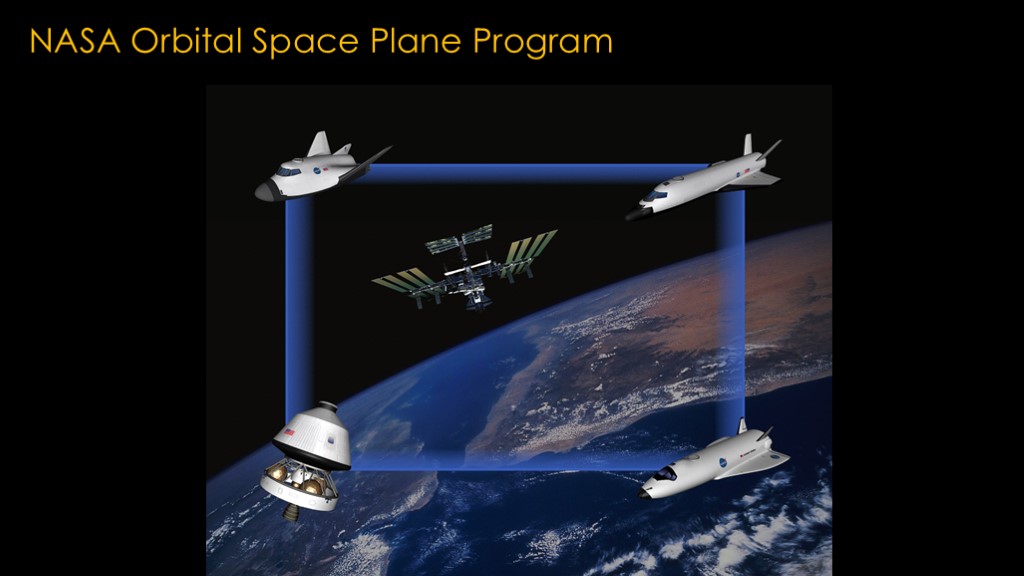

In the early 2000s, NASA had an orbital space plane program that would have launched small crew and cargo vehicles on commercial launchers to augment the space shuttle. These space planes would have worked well to serve ISS.

And yes, one of them is a capsule. NASA was okay calling that a space plane, and so am I.

The orbital space plane program morphed into the crew exploration vehicle for the constellation program. There would be two vehicles built by two separate contractors and flown to see which one was the best deal for NASA to purchase. This Lockheed Martin design would have launched on top of a commercial launcher and had both earth orbit and lunar variants.

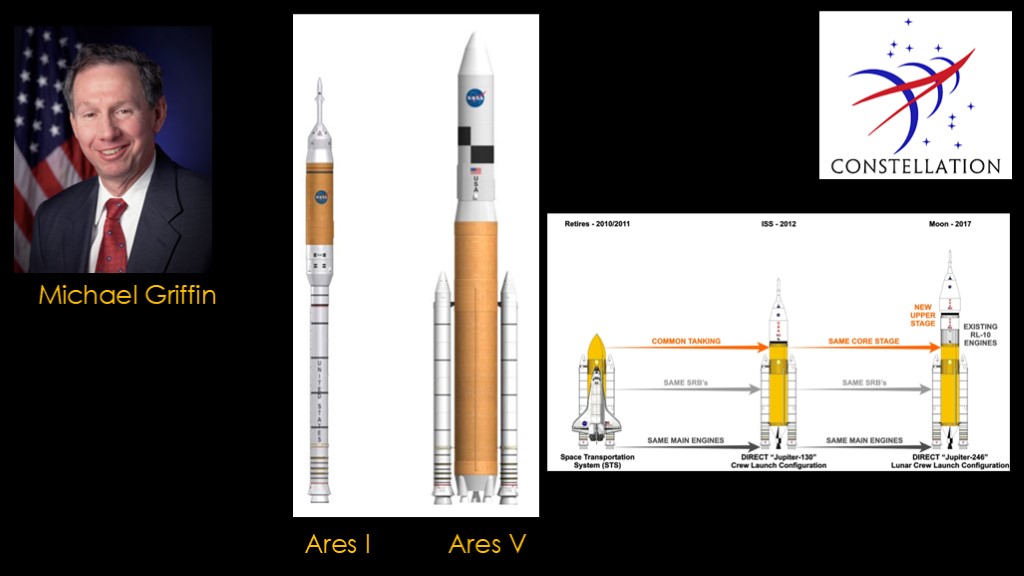

When the constellation program started, new NASA administrator Michael Griffin restructured the program to be a capsule-based design that was too heavy to be launched on the commercial launchers. This would eventually be renamed to Orion.

If that rescope hadn't happened, the crew exploration vehicles might have been a valid solution to carry crew and cargo to ISS. COTs would not have been needed.

Administrator Griffin mandated that the rockets used in the constellation program would be shuttle derived.

That gave us the crewed Ares I that used a solid rocket booster derived from shuttle, a new second stage, and the orion capsule on top. It also gave us the Ares V cargo vehicle to perform the heavy lifting required for the moon program.

While Ares I was considered a solution to get astronauts to ISS, using a moon capsule for that mission was a poor choice in terms of complexity and expense. There was no solution to fly cargo to the ISS in constellation.

There was a competing shuttle-based design known as "direct" or "Jupiter" that would use shuttle components with as little modification as possible. NASA also could have developed a "clean sheet" solution for ISS cargo.

Any cargo solution available early might have meant that COTs was not required.

Scenario 3: What if SpaceX did not succeed at COTs?

This one is going to be a bit complicated. I said that I wasn't going to talk about Falcon 1, but I've included the flights here to give a little context.

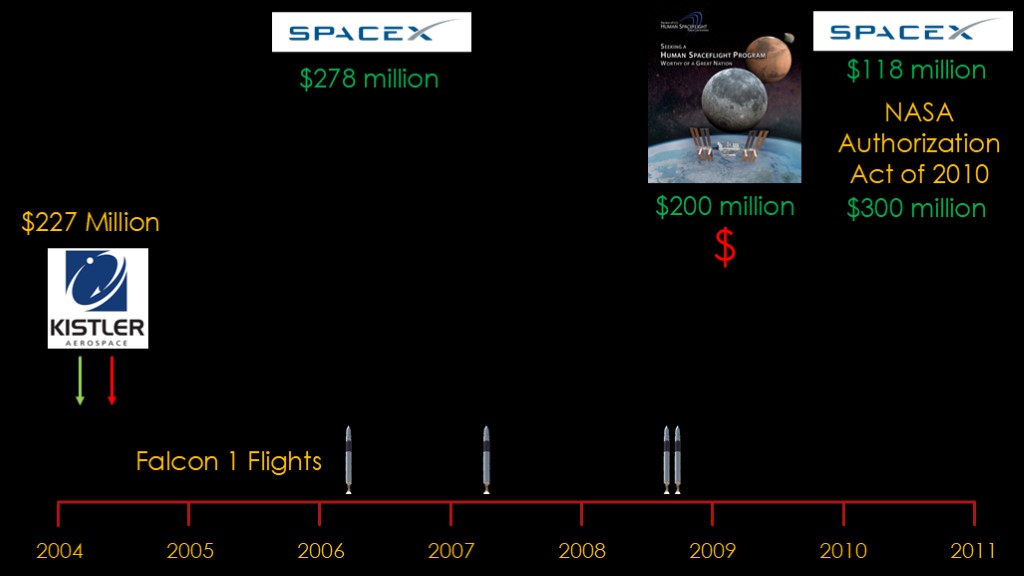

To start up the commercial space mandate, NASA decided to give $227 million to Kistler Aerospace in 2004. Kistler was headed by former NASA associate administrator Dr. George Mueller.

SpaceX protested to the general accounting office that this was an illegal non-competitive award, and the GAO quickly told NASA that there was no way they would win this suit. NASA pulled the award in June of 2004, and started the more formal process used for COTs.

The initial program got spun up in late 2005, with 6 semifinalists selected in May of 2006 and SpaceX selected as a phase 1 winner in august of 2006, with an award of $278 million. I'm going to ignore the other participants in COTs.

Note that between the startup of the program and the selection, SpaceX launched their first Falcon 1 flight. If NASA had started COTs 6 months earlier, NASA would have been making their decisions before Falcon 1 had gotten off of the pad. It's not clear that SpaceX would have been a winner without that technical achievement, and this is a way that SpaceX might not have gotten the COTs contract.

There was one more problem with COTs. NASA had arbitrarily decided that $500 million was enough money for two participants, and it was apparent by 2009 that the program would not be a success without additional money. This was problematic because Congress hadn't been very excited about COTs during early appropriations.

The program was in trouble.

Then something unexpected happened. President Obama had set up the Augustine commission to review the current state of NASA's human spaceflight program, and the commission released their report, "Seeking a human spaceflight program worthy of a great nation", and in the congressional hearings that followed the release, commission members advocated giving an additional $200 million to the program.

Even more unexpectedly, when the NASA authorization act of 2010 came out of congress, it gave an additional $300 million to the program, and $118 million of that went to SpaceX.

Without that extra money it is unlikely that SpaceX's COTs contract would have been successful.

There was another issue...

The original concept was that the contractors would finish the development of their vehicles and then NASA would order flight vehicles to be used for actual resupply missions.

But shuttle was retiring in 2010, and NASA was concerned that the COTs contractors would not be nimble enough to start flying soon enough after shuttle retired, so they made a decision to push things forward and get the program up and running on much earlier.

The released a request for proposal in April of 2008, got the proposals and then made awards in December of 2008. Note that at the time when SpaceX needed to be figuring out what their firm-fixed price bid was for flying falcon 9 and cargo dragon, they had been only working on Falcon 9 for two years and had yet to reach orbit successfully with Falcon 1.

They were supposed to somehow figure out the operational costs for a vehicle that would not fly for two more years, in mid 2010.

Not surprisingly, they did not estimate as well as they had hoped and the operational CRS flights did not provide the profits they had planned on, leaving the company cash-strapped. This is why SpaceX raised their prices significantly for the CRS-2 contract.

This timing was an unfortunate choice by NASA that was unfair to both contractors - firm fixed price contracts are supposed to be used when the products are well understood, and that clearly could not be the case 4 years before the first flights to the space station.

Scenario 4: What if SpaceX did not get commercial launches?

(Add satellites next to Ariane..., show on next slide as well.

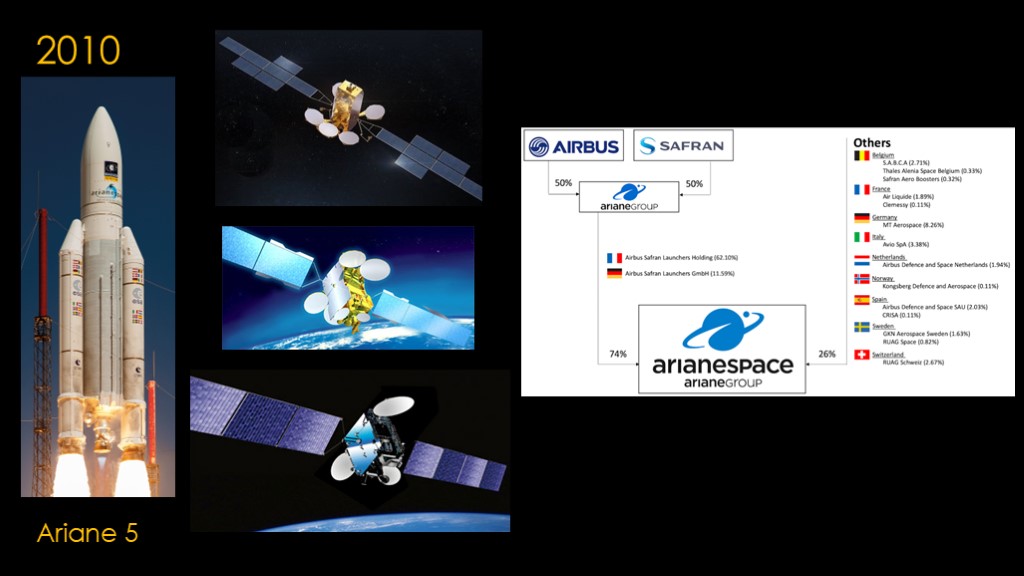

In 2010, Ariane 5 was flying consistently.

One the problems of Arianespace is that their production is spread across many countries and companies, and that means production planning is very complex and has a long lead time, so it's difficult for them to increase or decrease the flight rate.

This means they cannot easily respond to increased demand.

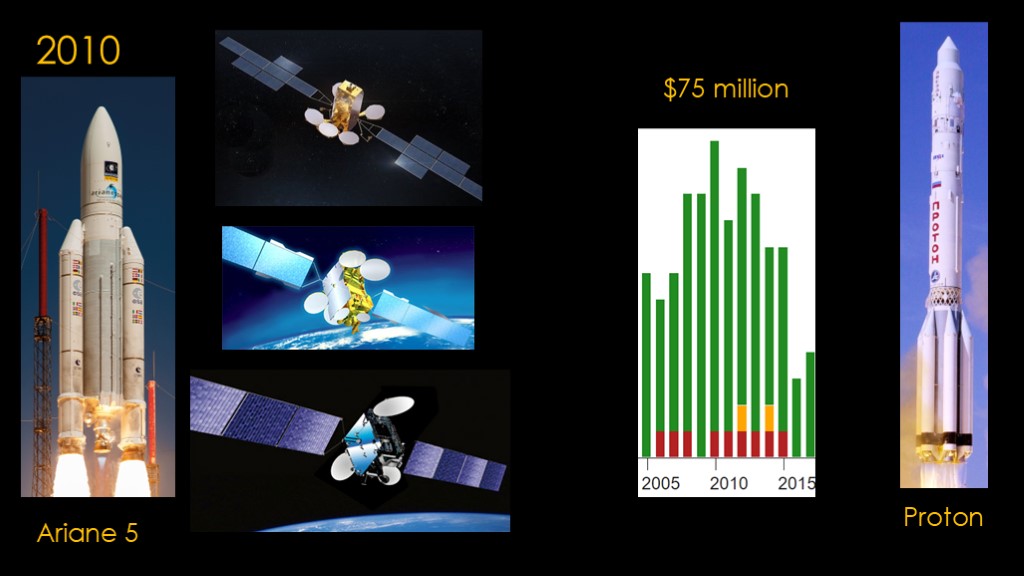

That left an opening for a competitor, and that competitor was the Russian Proton rocket.

It was priced around $75 million, which was an attractive discount on the Ariane price. The downside of proton was that it had a long history of poor quality, and if you flew on Proton there was a chance that your payload would not survive.

But there was enough backlog that customers would prefer to take their chances rather than wait years to get their satellite into orbit.

If Ariane 5 was able to fly more or Proton had better quality, the opportunity to launch these commercial satellites would not have existed.

This provided a market opportunity for SpaceX.

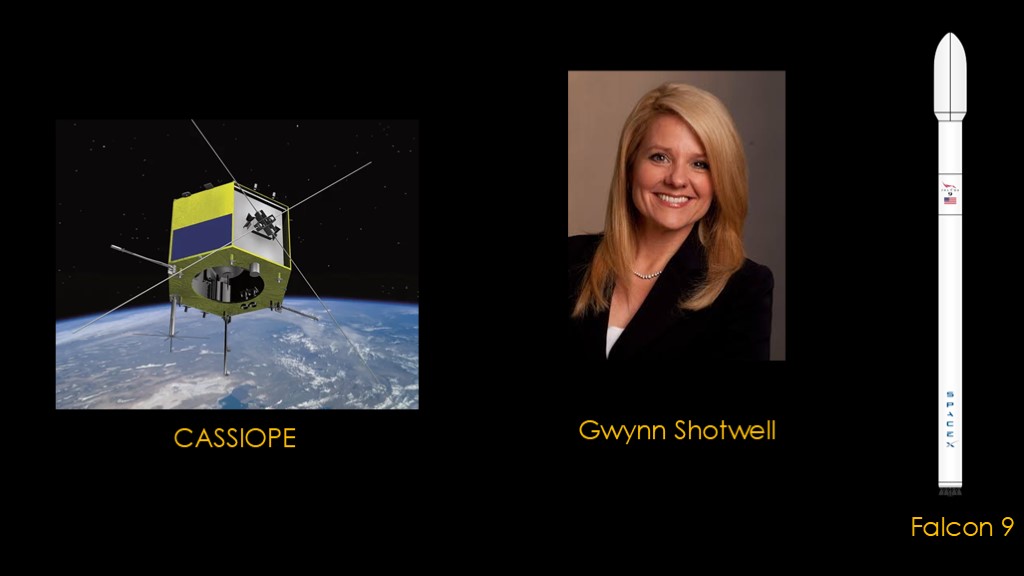

I said I was only going to talk about external factors, but I need to break that here.

If SpaceX did not have the skills of Gwynn Shotwell to sell launches on this new and unproven rocket, it is likely that they would not have been able to exploit this market.

Scenario 5: What if SpaceX could not launch for NASA and the department of defense?

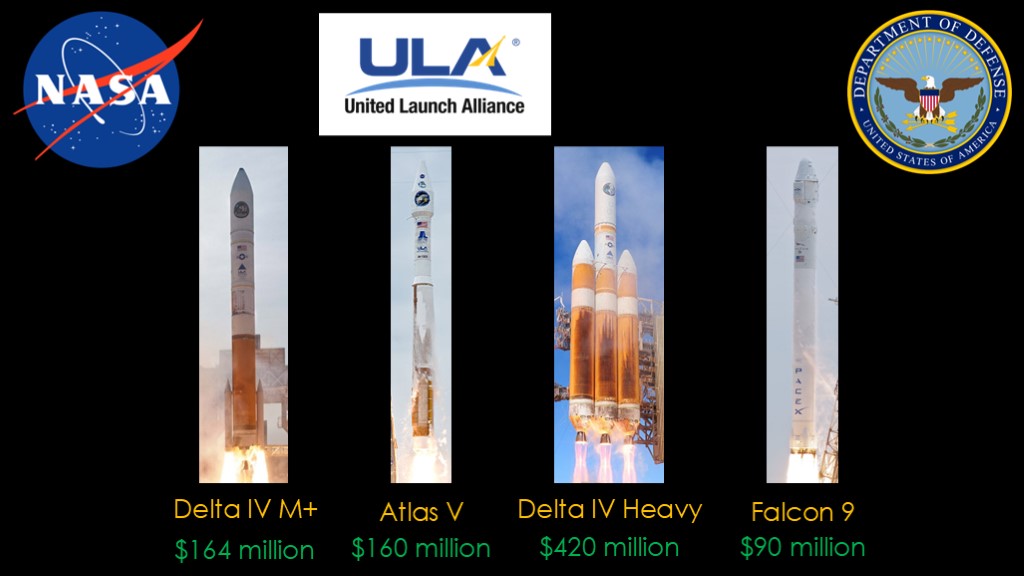

In 2010, if you were in NASA or the department of defense and you wanted to launch a payload, you had three rocket choices.

You could launch on the Delta IV Medium plus, the atlas V, or if you really needed a big payload to a hard destination like geostationary orbit, a delta IV Heavy. For these launches, you would pay $164 million, around $160 million, and a mind-boggling $420 million.

All of these rockets were manufactured by United Launch Alliance, a company that had a virtual launch monopoly on US government payloads since it was formed in 2006. You might think the high prices were due to a monopoly, but Lockheed Martin and McDonnel Douglass (before the Boeing merger) had been the two providers for the air force's evolved expendable launch vehicle program since 1994 and had found that having assured business with the government was a great opportunity to make huge profits.

Falcon 9 was able to enter this market because it was so much cheaper than the ULA rockets, costing perhaps $90 million for a government launch.

Entering this market took some time and some lawsuits, but it turned into a steady source of high profits for SpaceX.

If there had been a competitive US launch provider, this opportunity would not have been available.

What have we learned?

Space benefited from some unique circumstances that helped pay for falcon 9 and made it relatively easy for them to get launch contracts.

SpaceX saw these circumstances took advantage of them.

If you are evaluating other launch companies, note that NASA is not currently helping companies to build their rockets and instead of competing with Proton and ULA, new launch companies have to compete with SpaceX.

If you enjoyed this video, please send some lucky space rockets. I have calculated that for my salute to Falcon 9, I will 69 of these packages.